Anyone involved with Dynamics 365 Finance and Operations (whether a solution architect, development manager, or an X++ programmer) has likely heard that you cannot directly modify Microsoft’s base code.

In fact, the platform enforces an “extensibility” model – a replacement for the old practice of overlayering – to ensure that customizations don’t break when you upgrade.

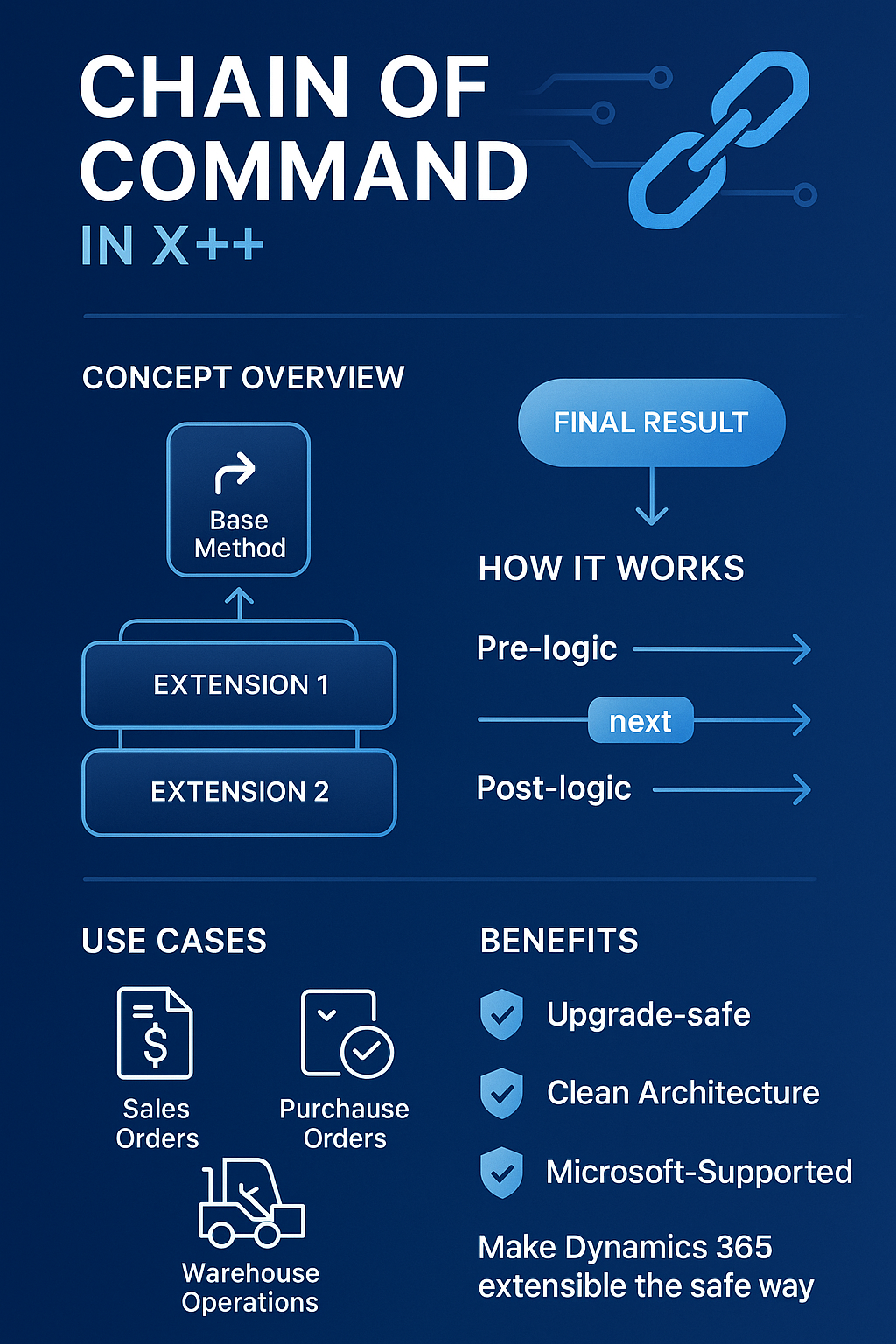

This is where the concept of x++ chain of command comes into play. Chain of Command (CoC) is Microsoft’s answer to safely injecting new business logic into standard processes without touching the original source code. It’s a design pattern (similar to the Chain of Responsibility) that lets your custom code wrap around the core logic, calling into the base implementation but adding your own behavior before or after it. The result is a loosely coupled customization approach that keeps your solution upgrade-safe and maintainable even as Microsoft pushes out updates.

Why Chain of Command Matters for Dynamics 365 F&O

From a high-level perspective, CoC is all about upgrade-safe extensibility – a cornerstone of modern D365FO development. If you’ve gone through any official d365 fundamentals training or even the dynamics 365 fundamentals training on Microsoft Learn, you’ve learned that overlayering (directly customizing Microsoft’s code) is no longer supported. Instead, we must extend standard functionality. Chain of Command is the primary mechanism to achieve this in X++. It allows partners and customers to extend or modify the behavior of standard processes (sales order posting, inventory updates, calculations – you name it) by writing extension methods that run in a chain with the base method. Because the base code is never actually changed, Microsoft can update the system and your CoC extensions will still be invoked in the upgraded environment. This model ensures that even heavily customized deployments can take platform updates with minimal fuss. For decision makers, the benefit is clear: you get the custom business logic you need, without sacrificing the ability to stay current with Microsoft’s improvements.

Beyond just being a technical requirement, Chain of Command also encourages good architectural practices. By design, CoC fosters a clean separation between standard logic and custom code. Your developers implement enhancements in isolated extension classes, which are then “woven” into the application execution at runtime. This loose coupling means the base application and extensions communicate through defined extension points, rather than one side hard-coding over the other. In simpler terms: CoC lets you plug in new logic like a USB drive, instead of soldering it permanently onto the motherboard. The purpose is to make customizations feel more like configuration – easily added or removed – instead of one-off hacks. Microsoft’s own documentation emphasizes that every public/protected method in X++ can act as an extension point, inviting developers to attach new behavior without altering the original code. This philosophy is a big shift from earlier ERP customizations and is crucial knowledge for both beginners and experienced folks in the Dynamics ecosystem.

How Chain of Command Works (Purpose & Syntax)

So, how does one actually use Chain of Command in X++? The mechanism is often described as “method wrapping.” A developer creates a class extension (a new class marked with an attribute pointing to the class being extended) and then writes a method with the exact same signature as the base method they want to augment. For example, if there’s a standard class BusinessLogic1 with a method doSomething(int arg), an extension class can be declared as:

final class BusinessLogic1_Extension

{

public str doSomething(int arg)

{

// custom pre-processing

var result = next doSomething(arg + 4);

// custom post-processing

return result;

}

}

In this snippet (based on Microsoft’s examples), the ExtensionOf attribute tells the system which class we’re extending, and the next keyword calls the next element in the execution chain. The call to next doSomething(arg + 4) will eventually invoke the original BusinessLogic1.doSomething method – but not before giving any other extensions a chance to run as well. Essentially, all extensions and the base method form a call chain. The runtime will invoke one of the extension methods first (the order is not guaranteed if multiple extensions exist), then next calls will cascade through any additional extensions, and finally the actual base method executes. Every link in this chain can add logic either before or after calling next, effectively surrounding the core behavior with custom code. This is why CoC is sometimes likened to having built-in “pre” and “post” event hooks – the code before next acts like a pre-event, and code after next acts like a post-event.

There are some syntax rules and requirements to be aware of. The extension class must be marked final (so it itself can’t be further extended) and must follow the naming convention of ending in _Extension. The method in your extension must have the same signature and access modifier as the base method. For instance, if the base method is public and static, your extension method must also be public and static. If the base method has default parameters, you omit the default value in your extension’s signature (just include the parameter). And critically, you must call next in your extension method (except in special cases discussed later) – failing to call next will result in a compile error or unexpected behavior because you’d be short-circuiting the chain. Microsoft enforces that next be called unconditionally in almost all cases, and it has to be in the first level of the method body (you can’t wrap the next call in an if or a loop, and you can’t skip calling it). This ensures the base logic always executes and all extension code in the chain contributes to the final outcome.

One notable exception is if the base method is marked with the attribute . A replaceable method is essentially Microsoft saying, “It’s okay if an extender wants to completely override this logic.” In those cases, the compiler will not force you to call next. However, even for replaceable methods, the best practice is to only skip the next call conditionally – for a specific reason – rather than always bypassing the base method. Skipping next means your extension might choose to not execute the standard logic at all (effectively replacing it). This can be powerful (for example, to totally change a calculation algorithm) but should be done with caution. In general, unless you have a replaceable method with a very targeted reason to override it, you will always call into the base implementation as part of your CoC extension. This pattern, enforced by X++, guarantees that updates or other extensions still get the original intended behavior unless explicitly superseded.

To support many extensibility scenarios, CoC works not just on standard classes, but also on tables, forms, form controls, data sources, and data entities. The syntax differs slightly in those cases (you use tableStr(), formStr(), etc., inside the ExtensionOf attribute), but the idea is the same. For example, you can extend a table object’s methods by writing class SomeTable_Extension { … }. You could wrap a form’s data source method (like a form’s data source validateWrite) by targeting the form data source via . CoC was eventually extended to cover form controls and data source fields as well (so you can even intercept a form control’s modified or clicked method through an extension). A quick illustration: imagine a form field where you want to run custom code when its value changes – you could create an extension for that form data field and wrap its modified() method to add your logic, then call next modified() to let the standard behavior occur. Under the hood, all of this is compiled into metadata that the runtime uses to weave your code into the base application execution. The beauty is that Microsoft’s model allows these extensions without requiring you to recompile or alter the original modules – your package just augments the base one at runtime.

Chain of Command vs. Event Handlers – What’s the Difference?

If you have a background in older Dynamics AX or early versions of D365FO, you might recall using event handlers to customize logic. Event handlers (pre-events and post-events) were an earlier approach to inject code before/after a base method’s execution, by subscribing to events rather than overriding the method. In D365FO today, both approaches exist, but Microsoft generally recommends Chain of Command for most scenarios of extending business logic on methods. One Microsoft MVP famously put it: “Pre- and post-method event handlers should be avoided whenever possible. CoC is a better way.” This is because CoC is more powerful and more natural to the object-oriented flow – your extension runs in the context of the class instance, meaning you can access all the class’s variables and state directly with this (or element on forms). By contrast, event handler methods are static, often requiring you to fetch the instance from parameters like XppPrePostArgs or a sender object. Simply put, writing a CoC extension feels like writing part of the original method, whereas an event handler is a separate listener that gets a snapshot of things. This makes CoC extensions typically easier to read and maintain, since they look like regular overrides where you clearly see the sequence of logic (custom code -> call next -> more custom code) in one place.

That said, event handlers haven’t gone away – and they do have some particular uses where they shine. Certain scenarios in D365FO still rely on events, especially delegates (published events in the code that you subscribe to) or form control events. Also, event handlers can be more flexible in a few ways. For example, you can have one handler method respond to multiple events (perhaps centralizing logic for several forms or tables in one class), and you can even attach or detach handlers at runtime if needed. You can’t do that with CoC – an extension is statically declared for a specific method via attributes. Moreover, if you want to catch an event that isn’t tied to a specific method override, event handlers are the way to go. A good practice is to use CoC for modifying or extending the core logic of methods, and use event handlers for things like reacting to framework events (for instance, a record being inserted via a data event, or a form’s OnInitialized event). One community expert summarized it well: CoC is usually easier and more powerful, but event handlers have some benefits too – they allow more dynamic and one-to-many relationships (multiple handlers on one event, or one handler for multiple sources). In fact, you might sometimes design a single handler class that contains several related handlers (say, all validation events for a form’s various controls) for organizational convenience.

However, when it comes to extending business logic in an upgrade-safe way, Chain of Command is generally the go-to approach in Finance and Operations. Microsoft’s own extensibility guidelines favor CoC because it ensures the base code runs unless explicitly overridden, and it provides a structured way to wrap logic, which aligns well with their continuous update model. Event handlers (particularly the pre/post method ones that essentially duplicate what CoC can do) are therefore considered a fallback – to be used only in situations where CoC isn’t applicable. One such situation might be if the method you need to influence isn’t extensible (for example, it’s a private method or not invoked in a way you can intercept), but maybe that method fires a delegate or updates a data source that has an event – then you use the event. Another scenario is if multiple pieces of logic need to hook into something without any direct relationship – events can broadcast to many listeners, while CoC chains are inherently a single chain of calls. In summary, CoC vs. event handlers isn’t an absolute either/or – they are complementary tools. But for core business process customizations in X++, CoC is the modern, preferred pattern, offering a cleaner, more upgrade-resilient path. Microsoft Learn documentation and training materials for D365FO development heavily emphasize mastering CoC alongside traditional event handling, so your team should be comfortable with both. Just remember: if you can accomplish it with a CoC method wrap, that’s likely the better choice than writing a pre/post event handler for the same thing.

Real-World Scenarios: CoC in Action for Business Processes

It’s all well and good to talk theory, but how does Chain of Command really help in day-to-day business customizations? Let’s explore a few scenarios in sales, purchasing, and warehouse management where CoC shines:

- Sales Order Customizations: Imagine your company has a policy that whenever a sales order line is added, the system must check the customer’s credit rating and pop a warning if the rating is missing. In standard D365, when you add a line to a Sales Order, a framework class (let’s call it SalesLineType) handles the line insertion. Using CoC, a developer can extend the SalesLineType.insert(…) method to include the custom credit check logic. In practice, this was demonstrated by a Dynamics 365 developer who created an extension for SalesLineType.insert – querying the customer’s credit rating, throwing an info message if it was blank, and then calling next insert() to let the normal insert process continue. The result? The sales line is still created as usual (because we didn’t break the chain), but our custom validation runs in-line with the process. From the user’s perspective, it feels like a native part of the system’s behavior. We didn’t have to copy-paste or modify the base code for inserting sales lines; we just wrapped it. Another common sales scenario is adding validation or defaults when confirming or invoicing a sales order. Suppose you need to integrate an export control check during sales order confirmation. Microsoft’s documentation itself guides you to “create a chain of command extension of the COOValidateSalesTable class and override the appropriate method” to inject your custom checks during the confirmation posting process. This kind of example shows CoC being used in real-life projects: you extend standard posting logic (like sales confirmation) to, say, log extra data or enforce additional rules, all via a wrapper method that calls into the base posting routine. Because CoC runs your code and then calls next, the normal flow (updating order status, generating invoices, etc.) still happens, but your custom step is seamlessly included.

- Purchase Order Customizations: The purchasing process often needs tweaking to match business needs. Consider a case where you want to enforce that a certain field (e.g. Buyer group or an internal approval code) is filled in before a Purchase Order can be confirmed or approved. Without CoC, you might resort to adding scripts or event handlers on form controls. With CoC, you can do it more elegantly: for example, extend the validateWrite() method of the PurchTable (purchase order header table) to include your validation logic. An extension could call next validateWrite() (which runs all standard validations), and then check your custom condition – if the Buyer group isn’t set, you can return an error message to prevent saving. This way, you augment the built-in data validation with your own rules. Another scenario might be customizing the posting of a PO invoice – perhaps to trigger an external system update or apply some custom calculations. Using CoC, a developer could wrap the method that posts the PO invoice (for instance, an update or post method in the PurchFormLetter class hierarchy) and insert the custom code at the appropriate spot. The important thing is that these customizations ride along with the standard process. When Microsoft delivers a new update that might change how purchase orders are confirmed or invoices are posted, your extension calls next to execute Microsoft’s updated code and still performs your add-on logic around it. This dramatically reduces the effort of regression testing after upgrades, since you’re not monkey-patching the internals – you’re just plugging into official extension points.

- Warehouse Operations: The warehouse management module provides another rich playground for CoC. Warehousing processes (like releasing orders to the warehouse, creating work, posting shipments, etc.) often have very specific business requirements in different industries. Suppose you need to modify how the system allocates inventory on a sales order release – maybe you have a custom “slotting” logic or you want to prevent certain items from being released under conditions. With CoC, you could extend the method that creates the warehouse work for a release (for example, a method in class WHSWorkCreate or similar) and inject your custom allocation logic before or after the standard logic. By calling next, you ensure all the complex standard warehouse allocation logic still runs, and you either pre-process the data going in or post-process the work created. Another concrete example: consider a requirement that during shipment confirmation, if the load contains hazardous materials, you need to perform an extra verification step. You could find the method in the base code that finalizes a shipment confirmation and wrap it. In your extension, you run your hazard check at the top; if it fails, maybe you log an issue or prevent final confirmation (perhaps using a base method so you can conditionally skip the core confirmation). Otherwise, you call next confirmShipment() and let the standard process complete. In one fell swoop, you have added a bespoke business rule to the warehouse operation.

Developers in the Dynamics community have shared numerous such examples. One team used CoC on a form data source method of the Purchase order form to dynamically enable or disable a button based on the PO’s status. Another example extended the SalesTable form’s data source active method to control UI elements when the record’s state changed (e.g., toggling fields when a sales order was invoiced) – something you could also do with event handlers, but the team found it cleaner with one CoC method instead of two separate event handlers for activate/deactivate logic. The pattern repeats across scenarios: when you need to tweak how the system behaves in a standard process (be it sales, purchasing, inventory, manufacturing, etc.), you look for an appropriate method that you can wrap with Chain of Command. By doing so, you’re lining up your code in the execution sequence of that process. The standard process doesn’t know any different – it runs as if it was coded to do your extra steps. And if multiple solutions extend the same process, each extension gets its turn in the chain (though remember, the order of execution among multiple extensions is undefined – which leads us to some considerations in the next section).

Limitations, Gotchas, and Best Practices

Chain of Command is powerful, but it’s not magic – there are important limitations and best practices to understand. First and foremost, not every method is extensible. CoC works on public and protected methods. If a method is private or the application doesn’t expose a suitable extension point, you can’t directly wrap it. Microsoft has been gradually making more of their code extensible (and you can log extensibility requests for Microsoft to open up certain functionality), but you may occasionally hit a wall where the method you want to augment isn’t available for extension. In such cases, you might resort to an alternate hook (perhaps an event or a different extension point) or wait for a platform update that marks it extensible. Additionally, some technical restrictions exist: for example, you cannot use CoC to wrap methods on extension classes themselves (i.e., you can’t chain an already chained method – CoC only targets base implementations). Historically, there was a limitation that methods on nested form controls or data source fields weren’t fully wrap-supported until later platform updates. By now, many of those gaps have been filled (Platform Update 16 added support for form data source and control method wrapping), but it’s always wise to check the latest Microsoft documentation for any quirks. For instance, as of a couple years ago, if a developer tried to wrap a purely X++ method on a form’s nested control, it might compile but not execute at runtime – a frustrating gotcha that was marked for future enhancement. These edge cases aside, most common classes, tables, and forms in Finance and Operations have been made extensible to support CoC.

Another limitation to keep in mind is the execution order when multiple extensions exist. Microsoft explicitly notes (and many blogs reiterate) that if there are several CoC extensions on the same method, the order in which they run is essentially random. You cannot rely on being the “first one” or “last one” in the chain. The platform might choose any extension to run first, then calls next to move to another, and so on, until finally the base method is called. This means your extension code should be written defensively and not depend on sequence relative to other extensions. If two different ISVs or teams extend the same method, they should ideally not conflict (each should call next and not assume something about the other’s presence). For decision makers, this is worth noting when evaluating ISV solutions: if two add-ons both override the same process via CoC, they will both execute, but their interplay might need testing since you can’t set which runs first. It’s a far cry better than outright code conflicts (which overlayering would cause), but it’s still a consideration for quality assurance.

Now, regarding best practices, Microsoft and seasoned developers have a few to share:

- Always call next (unless truly intended not to): We touched on this, but it’s the golden rule. The system even enforces it in most cases. If a method is not replaceable, you must call next or your code won’t compile or will break runtime expectations. Even if a method is replaceable, think twice before omitting next. Ask, “Am I replacing the standard logic, or just augmenting it?” If it’s the latter, call next so you don’t cut out important behavior. Only bypass when you’re sure you need to override entirely – and even then, often do it conditionally (for example, skip base call only for certain records or conditions, otherwise still call it).

- Keep extension code lean and efficient: CoC inserts your code into potentially performance-sensitive processes. A poorly written extension (e.g. one that does an extremely heavy calculation on every single order line insertion) could slow down the system. Follow good coding practices – minimize database calls in tight loops, avoid locking issues, and so on. Also, because all extenders run, your code is adding to the cumulative work done for that process. It’s usually negligible when done right, but be mindful in hot paths.

- Follow naming and structural conventions: Use the _Extension suffix for classes and the correct ExtensionOf(…) attributes as required. These aren’t just formalities – the compiler looks for these patterns. For example, if you leave off the “_Extension” in the class name, the build will throw an error because it doesn’t recognize it as a valid extension class. Similarly, match method signatures exactly, including static if needed, or your extension won’t hook up. Microsoft’s best practice is also to put extension classes in their proper packages and namespaces, typically in a separate model from the base code. Organize your extensions logically (perhaps mirror the structure of what you’re extending for clarity).

- One extension per class (and method): You’ll create a separate extension class for each core class or table you extend. Resist the temptation to lump unrelated extensions together. For instance, don’t stuff both a SalesTable extension method and a CustTable extension method into one class – even if it would compile, it’s clearer and more maintainable to keep them separate (and required if the names are to end with the correct object name + _Extension). Each method you want to wrap will be its own method in the appropriate extension class. This granularity is good: it forces clarity on what exactly you are extending and why.

- Use event handlers where appropriate: As discussed, if you need to handle a delegate or do something outside the scope of a single method’s logic, use the event handler. A typical example is reacting to the system’s OnDatabaseLog event or a workflow approval event – CoC can’t help there, but a handler can. Also, if you have a cross-cutting concern (like logging every time any form is opened), events or the SysExtension framework might be better suited. CoC is great for targeted method augmentations.

- Stay informed with Microsoft’s guidance: The Dynamics 365 product team and community continually share updates and recommendations on extensibility. Microsoft Docs (a.k.a. Microsoft Learn) is the authoritative source – for example, the docs highlight checklists and patterns for extensibility to ensure you don’t introduce breaking changes or unsupported customizations. Microsoft Learn also offers hands-on labs and examples demonstrating CoC usage in various scenarios. Keeping your team up-to-date via these channels (rather than relying on how “we used to do it in AX 2012”) is crucial, because the platform evolves.

To wrap up, Chain of Command in X++ is the modern way to tailor Dynamics 365 Finance & Operations to your business needs. It supports a layered approach where Microsoft’s code, your custom code, and even third-party extensions all coexist without clobbering each other. For a beginner, CoC might seem magical – you write a method with the same name in a new class, and somehow the system runs it. For an intermediate developer, it becomes a go-to pattern – the first tool you reach for to extend functionality. And for experts and architects, CoC is a fundamental piece of the extensibility strategy – enabling functional richness while preserving technical integrity of the application. High-level decision makers should care about Chain of Command because it directly impacts the TCO (Total Cost of Ownership) of customizations: it makes upgrades cheaper and easier, encourages better code practices, and reduces dependency on risky modifications. With CoC, you get the best of both worlds – a standard cloud ERP that can advance with Microsoft’s continuous improvements, and a bespoke system that can still meet the unique demands of your business. In a sense, mastering CoC is not just a technical necessity (for developers), but a strategic advantage (for organizations) in the Dynamics 365 landscape. Microsoft’s official docs and training materials underscore this, and the community’s blogs are full of real-life stories confirming it. So whether you’re coming from a background of d365 fundamentals or diving deep into X++ code, embracing Chain of Command is essential to make Dynamics 365 F&O truly work your way – safely, and for the long haul.

Have a Question ?

Fill out this short form, one of our Experts will contact you soon.

Talk to an Expert Today

Call Now