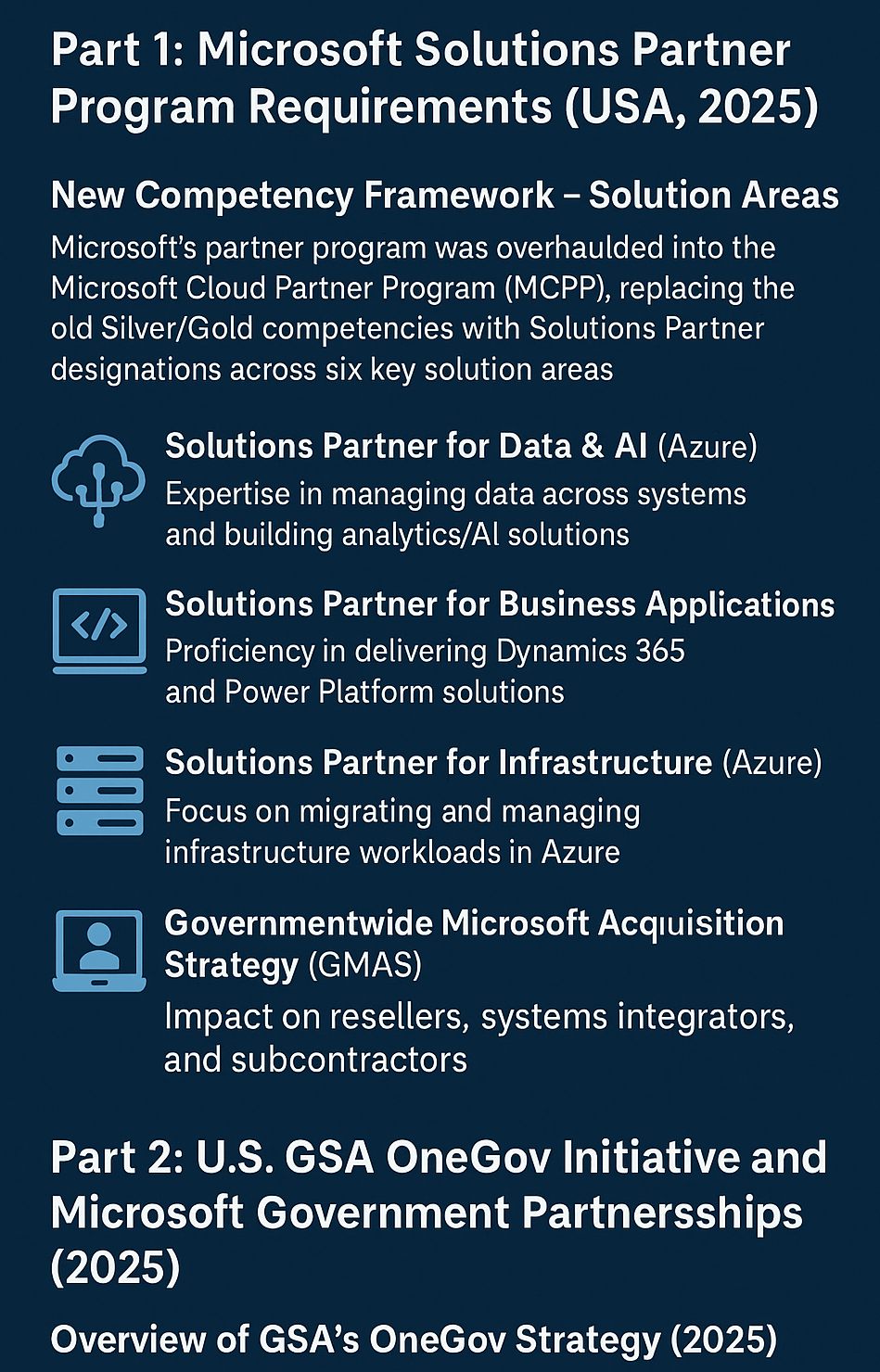

New Competency Framework – Solution Areas

Microsoft’s partner program was overhauled into the Microsoft Cloud Partner Program (MCPP), replacing the old Silver/Gold competencies with Solutions Partner designations across six key solution areas. So fulfilling the microsoft solution partner azure certification september 2025 is quite different now in August 2025 and beyond especially compared to before.

Each designation aligns with a high-demand cloud solution area and signifies broad capability in that domain:

- Solutions Partner for Data & AI (Azure) – Expertise in managing data across systems and building analytics/AI solutions on Azure.

- Solutions Partner for Business Applications – Proficiency in delivering Dynamics 365 and Power Platform solutions (CRM, ERP, low-code apps).

- Solutions Partner for Digital & App Innovation (Azure) – Skills in helping customers modernize applications across cloud, on-premises, or edge with Azure’s developer tools.

- Solutions Partner for Infrastructure (Azure) – Focus on migrating and managing infrastructure workloads in Azure (datacenter modernization, cloud infrastructure).

- Solutions Partner for Modern Work – Demonstrated ability to boost productivity and enable hybrid work with Microsoft 365 (Office 365, Teams, Windows 11, etc.).

- Solutions Partner for Security – Broad capability in deploying Microsoft security, compliance, and identity solutions to protect identities, devices, data, apps, and infrastructure.

Each Solutions Partner designation comes with a badge and listing in the partner directory, helping customers find qualified partners in that area. Notably, as of January 2025, the legacy Microsoft Partner Network competencies and Action Pack have been retired in favor of this new model. Achieving a Solutions Partner designation is now the primary way to showcase Microsoft expertise at the organization level (with optional specializations available to prove deeper technical focus in sub-areas).

Partner Capability Score – Points-Based Scoring System

To become a Solutions Partner, a company must earn a sufficient Partner Capability Score in the relevant solution area. The score is a points-based system measuring performance, skilling, and customer success. Each solution area has a maximum of 100 points, and a partner needs at least 70 points (out of 100) to qualify, with >0 points in each category (you cannot score zero in any category). This ensures partners have balanced strength – you cannot rely solely on certifications or sales alone. The scoring framework is summarized as follows:

- Performance (Partner Performance) – Measures the partner’s success in expanding Microsoft’s customer base. The primary metric is net new customer additions in the last 12 months. Points are awarded for each eligible new customer won (with any losses subtracted), up to a maximum (e.g. in Azure areas, ~10 points per new customer, capped at 30 points). Each solution area defines what counts as an “eligible” new customer (for example, an Azure customer generating a minimum Azure consumption, or a Modern Work customer with a certain number of seats). This performance category typically contributes up to ~20–30 points of the score in most designations.

- Skilling (Technical Skilling) – Assesses the partner’s technical expertise through Microsoft certifications held by staff. It has two sub-metrics: Intermediate certifications (generally associate-level certs) and Advanced certifications (expert-level certs). Microsoft defines a set of relevant certifications for each solution area, and points are earned based on the number of individuals holding those certs. There are thresholds for maximum points – for example, to get full points, an Enterprise partner might need ~10–20 certified individuals (fewer for SMB-focused partners). Importantly, at least one certification in each sub-metric is required (you need at least one intermediate and one advanced cert holder to avoid a zero in either category). The specific cert exams that count are updated periodically as Microsoft retires or introduces exams. We detail required certs below. Skilling often accounts for a large share of points (e.g. up to 40 points in some Azure tracks).

- Customer Success (Customer Success) – Gauges the partner’s success in driving usage and successful deployments of Microsoft solutions in their customer base. Typically split into Usage Growth and Deployments metrics. “Usage growth” measures year-over-year increase in consumption of Microsoft cloud services by the partner’s customers (for Azure, growth in Azure consumed revenue; for Modern Work, growth in M365 active usage or seats; etc.). “Deployments” measures the breadth of product/workload deployments across customers – essentially how many customers you have helped adopt a given Microsoft workload or service. Points are awarded for achieving certain growth percentages or deployment counts, up to defined thresholds. This category encourages partners to not just sell licenses, but ensure customers are successfully using the technology. Together, customer success metrics often comprise ~30 points of the total.

Multiple Tracks (Enterprise vs. SMB): Microsoft recognizes that partners serve different customer scales, so for five of the six solution areas (all except Security and Modern Work) there are two attainment tracks – Enterprise and Small & Medium Business (SMB) – with different point thresholds tailored to partner size/customer profile. Partners are automatically assigned a track based on the size of customers they sell to (for Modern Work and Security, Microsoft evaluates both tracks and uses whichever score is higher). For example, an SMB-track partner might need fewer total certifications or smaller customer consumption levels to earn the same points, recognizing their smaller scale. This makes the program attainable for boutique partners focused on SMB, while still challenging larger partners on the enterprise track. In all cases, however, the 70-point minimum (with no category zeros) applies to attain the designation.

Required Certifications and Skill Requirements

A critical part of the Solutions Partner requirements is having team members with relevant Microsoft certifications. Each solution area specifies certain certifications that count toward the skilling points. Generally:

- Intermediate (Associate-level) certifications – e.g. role-based certifications like Microsoft Certified: Azure Administrator Associate, Azure Developer Associate, Security Administrator Associate, Power Platform Functional Consultant Associate, Microsoft 365 Administrator Associate, etc., depending on the solution area. These prove proficiency in core tasks and usually form the bulk of the skilling points. For instance, for Azure-related designations, “Azure Administrator Associate” (AZ-104) is often a foundational requirement (e.g. in Data & AI and Infrastructure tracks, at least 1–2 people must have this cert). In Modern Work, intermediate certs include Microsoft 365 Certified: Teams Administrator Associate, Identity and Access Administrator Associate, Endpoint Administrator Associate, etc.. In Business Applications, intermediate certs might include Dynamics 365 Functional Consultant or Power Platform certifications.

- Advanced (Expert-level) certifications – e.g. Microsoft Certified: Azure Solutions Architect Expert, Azure DevOps Expert, Microsoft 365 Certified: Enterprise Administrator Expert, Dynamics 365 Solution Architect Expert. These are higher-tier credentials that demonstrate deeper expertise. Most solution areas require at least one or two individuals with an expert cert. For example, in Azure solution areas a partner must have people certified as Azure Solutions Architect Expert in addition to the administrator certs. For Modern Work, the key advanced cert is Microsoft 365 Enterprise Administrator Expert. In Security, an example advanced cert is Azure Security Engineer or Identity and Access Administrator Expert.

Microsoft provides a detailed list of which specific exams count for each designation on their partner site. As of 2025, many of the certification requirements have been updated to include new Microsoft AI and security certifications (aligning with emerging technologies), and older exams are retired on a rolling basis (with grace periods during which retired certs still count toward your score). Partners must keep their team’s certifications up to date – ensuring staff renew expiring certifications and earn new ones as required – to maintain their skilling points each year.

Licensing Paths and Program Enrollment: To participate in the Microsoft Cloud Partner Program and attain a Solutions Partner designation, partners must enroll in the program (via Microsoft Partner Center). The program itself is free to join, but obtaining the designation and benefits requires purchasing a Solutions Partner benefits package (annual fee) once you qualify. In the U.S., the annual fee is approximately $4,730 USD per year – about the same as the old Gold competency fee. This fee is paid after you have met the score criteria, in order to “unlock” the designation status and access the benefits. Notably, one annual fee covers all Solutions Partner designations your company attains in that year (you do not pay per designation). If you earn additional solution area designations later, Microsoft does not charge extra that year. At program renewal (your anniversary date), you need to reconfirm you still meet the requirements (e.g. maintain 70+ points during the year’s eligibility window) and pay the renewal fee to continue as a Solutions Partner. (For partners not yet ready to attain a designation, Microsoft now offers Partner Success benefits packages as a replacement for the retired Action Pack – these provide a set of internal-use licenses and support for a fee, as a stepping stone until you qualify as a Solutions Partner.)

Benefits of Becoming a Solutions Partner

Achieving a Solutions Partner designation in 2025 confers a portfolio of benefits and opportunities that can greatly help a partner’s business. Key benefits include:

- Product licenses and Cloud Credits for Internal Use – Partners receive internal use rights (IUR) for Microsoft software and cloud services. This includes licenses for Microsoft 365 (productivity suites), Dynamics 365, Power Platform, as well as Azure credits for development/testing, etc. The set of licenses has been expanded in 2025 to include new products like Microsoft 365 Copilot, Power Apps Premium, Defender for Endpoint, GitHub Enterprise, and more. These licenses enable partners to run their business on Microsoft technology and build demos/POCs for customers. Generally, the higher your partnership level, the more licenses/credits you receive. For example, upon attaining a Solutions Partner designation (and paying the fee), partners get a bundle of software seats and Azure credit allotments to use internally.

- Go-To-Market (GTM) Support and Partner Marketing – Microsoft provides marketing resources to help Solutions Partners generate demand and credibly present themselves to customers. This includes eligibility to be listed in the official Microsoft partner finder directory with the Solutions Partner badge (improving visibility to customers), use of the designation logo in marketing, and access to “campaign-in-a-box” kits, collateral, and Microsoft-led campaigns. GTM benefits also involve Microsoft-driven co-marketing or case studies with top partners, and guidance on improving your marketing strategy. Being a Solutions Partner signals credibility – Microsoft states it helps partners “differentiate your organization to customers in a competitive market”.

- Microsoft Co-Selling Opportunities – One major benefit is becoming eligible for co-sell programs with Microsoft. As a Solutions Partner, you can work directly with Microsoft’s sales teams on joint selling opportunities. Your solutions can be spotlighted in Microsoft’s commercial marketplace or sales channels. Microsoft’s field sellers are more likely to collaborate with partners that have proven competencies (Solutions Partner or specializations), referring customers to them or bringing them into deals. Co-selling can also mean access to Microsoft’s customer leads or inclusion in large enterprise proposals as an approved partner. In short, the designation “signals to your customers that your organization has verified skills…and a proven track record” and Microsoft in turn often steers business towards those partners.

- Technical Support and Advisory Services – Solutions Partners receive advanced support benefits. Microsoft offers a certain number of partner advisory hours or access to consultative pre-sales assistance to help design solutions for customers. Designated partners also typically get faster response times for support tickets through the Partner Center and can access expert troubleshooting for complex scenarios (this was previously known as Signature Cloud Support for Gold partners). Additionally, Microsoft conducts technical training events (like Certification Week bootcamps, technical webinars, etc.) exclusive or prioritized for partners in the program. There are also Partner University resources and practice exams to help your staff earn and maintain certifications.

- Financial Incentives – Attaining a Solutions Partner designation often unlocks eligibility for various incentive programs. Microsoft allocates funds and rebates for partners who drive cloud consumption or sell certain products. For example, Cloud Solution Provider (CSP) partners with a Solutions designation can earn incentive rebates on Azure consumed revenue or Microsoft 365 seat adds, as part of Microsoft’s incentive program (eligibility and rates are tied to partner level and designations). The Solutions Partner badge is a prerequisite for some of these incentives. Microsoft’s FY25 incentives noted that legacy Gold/Silver partners could keep incentives through their term, but going forward Solutions Partners are the ones eligible. The Dynamics Edge report confirms that with the designation, you gain “eligibility for incentives tied to that designation”.

- Training and Enablement Resources – Microsoft provides a wealth of training for partners. As a member of the program (even before achieving the designation), you have access to Microsoft Learn courses and partner training portals. Solutions Partners often get prioritized invites to Microsoft-led training like technical workshops, sales training, and special events (for example, the Microsoft Inspire conference and local partner events feature sessions for credentialed partners). In 2025, Microsoft emphasized new AI skilling initiatives for partners, aligning with the “AI Cloud Partner Program” evolution. Partners can also access Certification exam offers (discount vouchers) to help skill up their team. These resources help partners continuously upskill their workforce.

In summary, becoming a Solutions Partner in 2025 signals a partner’s commitment to excellence in Microsoft cloud solutions and comes with tangible rewards: software and cloud to run your business, support in winning deals (marketing and co-sell), financial perks, and ongoing training. Microsoft’s goal is to foster a competent partner ecosystem aligned to how customers buy in the cloud era. For a U.S.-based partner, the designation can be especially crucial to stand out among a large pool of Microsoft partners and to engage in lucrative federal or enterprise projects that often require an official Microsoft partner status.

Part 2: U.S. GSA OneGov Initiative and Microsoft Government Partnerships (2025)

Overview of GSA’s OneGov Strategy (2025)

In April 2025, the U.S. General Services Administration (GSA) launched the OneGov Strategy, a government-wide procurement initiative aimed at transforming how federal agencies buy IT goods and services. The essence of OneGov is centralization and standardization: instead of each agency acting alone, the federal government will act “as one” buyer to leverage its collective scale. In practical terms, this means deeper direct engagement with major technology vendors (OEMs) to get transparent, volume-based pricing, streamlined terms, and improved cybersecurity protections across the board. Historically, agencies purchased a great deal of software through third-party resellers, which led to fragmented contracts and inconsistent terms. Under OneGov, GSA is prioritizing direct relationships with Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) (like Microsoft, Oracle, Google, etc.) to deliver better outcomes on cost and security.

This strategy was catalyzed by presidential directives – it supports President Trump’s April 2025 Executive Order on ensuring cost-effective commercial solutions in federal contracts. (That Executive Order, Ensuring Commercial, Cost-Effective Solutions in Federal Contracts, reinforces that agencies should favor commercially available off-the-shelf products and consolidate purchases where possible.) OneGov is also aligned with an Executive Order on consolidating purchasing to eliminate waste. In GSA’s words, “the federal government should act as a single, coordinated enterprise when it comes to buying”, rather than siloed procurement.

Initial Focus and Phased Implementation: The first phase of OneGov (starting FY2025) is targeting IT software and cloud services – areas where redundant purchasing was common and savings can be immediately realized. GSA’s announcement highlighted that agencies will get easier access to IT tools with standardized pricing and terms in this phase. OEMs benefit from a more direct, predictable engagement model (no more guessing which reseller or contract each agency might use), and taxpayers benefit from a more efficient, secure IT enterprise. Early successes were noted: for example, GSA’s Office of IT Category had “reached government-wide agreements with Microsoft and Google” just prior to the OneGov launch. These agreements serve as proof-of-concept, showing the value of approaching the market as a unified customer.

Moving forward, OneGov will evolve to cover additional categories. GSA explicitly plans to expand the strategy into hardware, platforms, infrastructure, and cybersecurity services, among other common IT goods. Essentially, after tackling software licensing, GSA envisions using the OneGov approach for things like computers and devices, cloud infrastructure contracts, and even services like cybersecurity support. The long-term goal is for GSA to become the central hub for shared IT procurement across the federal government. This could eventually reshape or supersede some existing contract vehicles (such as agency-specific BPAs, Government-Wide Acquisition Contracts like SEWP or NIH CIO-CS, etc.), as common needs get aggregated under OneGov agreements. However, GSA has indicated it will implement the strategy in a flexible, collaborative way, engaging stakeholders and not abruptly upending current contracts. 2025 is just “Phase 1,” focusing on quick wins in software, with further phases to roll out over time.

Governmentwide Microsoft Acquisition Strategy (GMAS) – Microsoft’s Role

Microsoft is a cornerstone vendor for the federal government, and thus a key participant in OneGov’s first phase. In fact, even before OneGov was formally announced, GSA and Microsoft had been working on a dedicated initiative known as the Governmentwide Microsoft Acquisition Strategy (GMAS). On January 15, 2025, GSA finalized an Agreement in Principle with Microsoft under GMAS. This “landmark agreement” is essentially the Microsoft-focused piece of OneGov, establishing a unified set of terms for all agencies procuring Microsoft products and cloud services.

What GMAS Entails: The GMAS initiative brings together the 24 large federal agencies covered by the CFO Act to jointly discuss and agree on standardized terms, conditions, and pricing for Microsoft purchases. Instead of each agency negotiating separate deals (with varying discounts and clauses), GMAS sets consistent benefits to agencies regardless of size or purchasing method. According to GSA, the agreement focuses on several key elements:

- Standardized Terms & Conditions: Establishing and improving common T&Cs that will govern Microsoft procurements governmentwide. This ensures all agencies get the protections and favorable terms that the largest agencies might negotiate, leveling the playing field (and simplifying compliance for Microsoft).

- Enhanced Cybersecurity Measures: Implementing stronger, standardized cybersecurity requirements to address critical risks in government IT systems. Recent cyber incidents (such as breaches involving Microsoft software/services) heightened attention on security – the GMAS terms aim to embed robust security obligations (e.g. on data protection, incident response) directly into Microsoft’s federal contracts.

- Governmentwide Education and Support: Microsoft committed to provide enhanced support, training and workshops for agencies under this agreement. For example, Microsoft is offering a series of government-wide workshops on topics like cost management in Azure, governance of multi-cloud environments, cross-tenant collaboration, and conditional access controls. The goal is to help agencies maximize their investment, implement best practices, and improve their security posture using Microsoft solutions. This kind of broad enablement is part of the partnership not usually present in fragmented contracts.

Microsoft’s participation in OneGov/GMAS underscores its long-standing relationship with the U.S. government (over 40 years as a federal partner). By early 2025, Microsoft was one of the first major tech companies to align with the OneGov vision. In practical terms, the GMAS agreement is expected to translate into concrete contract vehicles that agencies can use. While the January announcement was an “agreement in principle,” GSA’s intent is to implement those terms via a government-wide contract mechanism. This could take the form of a new Blanket Purchase Agreement (BPA) or modifications to the existing GSA Multiple Award Schedule contract for Microsoft solutions. For instance, GSA might establish a BPA under the GSA Schedule IT category where Microsoft is the prime vendor, enabling all agencies to place orders with predefined discounts and clauses. Indeed, GSA’s Stephen Ehikian (Acting Administrator) noted that the strategy builds on the Microsoft and Google deals, and that GSA is becoming the “central hub” for these shared contracts. By mid-2025, agencies were already beginning to see immediate benefits: GSA cited stronger terms, enhanced cybersecurity, and improved support services for all agencies as outcomes of the Microsoft GMAS deal.

Impact on Resellers, Systems Integrators, and Subcontractors

One of the most significant shifts under OneGov is how it changes the role of traditional resellers and integrators in federal IT sales. The federal IT market has long relied on value-added resellers (VARs) – firms like Carahsoft, CDW-G, SHI, etc. – who hold contract vehicles (especially the GSA Schedule) and sell software licenses on behalf of OEMs that may not contract directly with the government. These resellers often provide ancillary services (integration, customization, support) and handle the complex compliance and contracting tasks for the OEMs. Under the legacy model, the reseller is often the prime contract holder, with the big software manufacturer in the background.

The OneGov strategy essentially “flips” that relationship. Going forward, the OEM (manufacturer) will be the prime contractor, and any resellers or integrators will serve as subcontractors or channel partners to the OEM. GSA officials have been clear that resellers are not being eliminated, but their role is being restructured. Lawrence Hale, Assistant Commissioner for IT Category at GSA, explained it this way: “While the contract may be with the OEM, there’s still a vital role for resellers and integrators to play as subcontractors or authorized partners… providing high-value services like onboarding, integration and training.”. In other words, agencies will buy the licenses or cloud services directly via a Microsoft or Oracle contract, but those OEMs can partner with small businesses and IT service firms to deliver implementation, consulting, and support. The OEM gets to interface directly with the government for the sale, and then brings in reseller partners as needed to service the customer.

This flip in roles has a few important implications:

- Clearing Up Accountability: Previously, if something went wrong – e.g. a major cybersecurity vulnerability in a software product – the government’s contract was with the reseller, not the OEM. Agencies had to go through the reseller to address issues, even though the reseller didn’t develop the software. Small reseller businesses were put in the awkward position of answering to federal customers about, say, a Microsoft Exchange breach. Under OneGov, with the OEM as prime, the government can hold the source vendor directly accountable for security issues and performance. Hale gave the example: is it fair to make a small business reseller answer for vulnerabilities in a major manufacturer’s software? – Now that burden shifts to the OEM, which clarifies responsibility. This is seen as a positive for both agencies and small partners: the agency gets direct recourse with the source vendor, and small IT firms aren’t on the hook for issues out of their control.

- Resellers as Service Providers: Rather than making margins simply on product resale, VARs will need to focus on the value-added services they can provide. GSA is signaling that success for resellers will come from evolving into specialists in implementation, customization, cybersecurity services, training, and other support roles. The “door is not closed” to resellers – those that provide genuine value will “still play an absolutely critical role” in the process. For instance, Microsoft (as an OEM prime) might still rely on its network of Microsoft partners (system integrators, consulting firms, etc.) to deploy solutions for an agency, but those partners would be subcontractors under Microsoft’s federal contract. We may see OEMs design authorized federal partner programs or contract teaming arrangements to include their top resellers in OneGov deals. Ultimately, GSA expects integrators to continue providing services like cloud migrations, managed services, and industry-specific solutions – but now in partnership with OEMs rather than as prime sellers.

- Small Business Participation: One concern in flipping this model is the impact on small businesses who used to be primes on, say, GSA Schedule contracts for software. GSA has small-business goals to meet. By making Microsoft the prime, one might fear small businesses get pushed out. GSA’s approach is to still involve small businesses as subcontractors to meet those goals. Hale noted that the relationship details (which partners an OEM works with, and how work is split) will be left “up to the OEM” and not dictated rigidly by GSA. Different OEMs may have different models – some might name a handful of resellers as exclusive fulfillment agents; others might keep an open ecosystem. GSA is likely encouraging OEMs to include diverse partners (small, disadvantaged businesses, etc.) in their fulfillment strategy to satisfy federal socioeconomic requirements. In any case, small IT firms can still thrive by aligning with OEMs as implementation partners. In fact, OneGov could reduce some risks for small businesses – as noted, they won’t bear contractual liability for the entire product stack, and can focus on delivering services where they excel.

In summary, OneGov reverses the traditional dynamic of federal IT contracting. OEMs like Microsoft, Google, Oracle are becoming the direct contractors to GSA, and resellers/integrators are relegated to subcontractor or channel partner roles supporting those OEM contracts. GSA officials acknowledge this is “disruptive” to the status quo, but they frame it as a positive disruption that will yield benefits (clearer accountability, better pricing, and still plenty of opportunity for partners to add value). Early feedback from OEMs has been enthusiastic – many large tech companies have wanted a more straightforward way to do business with government, and OneGov aims to “make terms and conditions as close as possible to commercial” to entice them. Resellers, on the other hand, are in “wait and see” mode, understandably, as this new model rolls out. But those who can pivot to service-centric offerings and team with the OEMs stand to continue prospering in the federal market albeit under a new arrangement.

Cybersecurity, Pricing, and Compliance Expectations under OneGov

A driving rationale for OneGov is to address inconsistencies in cybersecurity and compliance across many individual contracts. By negotiating one set of terms with an OEM, GSA can demand higher standards for security and uniform compliance provisions that every agency will benefit from. Under OneGov agreements (including GMAS with Microsoft), the contracts “include clearer, enforceable obligations on data protection, encryption, and incident response.”. This is a significant improvement: previously, some agency-level contracts might lack certain clauses or rely on reseller flow-downs. Now, GSA is baking in strong cybersecurity requirements up-front with the OEM. For example, Microsoft’s governmentwide agreement likely stipulates enhanced data encryption standards, breach notification and response timelines, vulnerability management, etc., that Microsoft must adhere to for all federal customers. These obligations are enforceable directly with Microsoft. It also likely addresses supply chain security (ensuring no risky code in updates), and requires compliance with federal cybersecurity mandates such as Zero Trust architectures and multi-factor authentication guidelines across Microsoft’s offerings. Essentially, consistent cybersecurity standards will be applied government-wide, rather than each contract having different terms.

Compliance and Certifications: Another expectation is that cloud services and software must meet federal compliance regimes like FedRAMP (Federal Risk and Authorization Management Program) and others. In the Oracle OneGov deal, for instance, Oracle highlighted that its cloud platforms achieved FedRAMP High authorization and even Department of Defense IL5/IL6 for classified data. We can expect similarly that Microsoft’s cloud offerings under OneGov (e.g. Azure Government, Microsoft 365 GCC High) are required to maintain FedRAMP High and DoD IL5 certifications. OneGov’s emphasis on cybersecurity means that OEMs must continually comply with evolving federal standards (like NIST SP 800-171/53, CISA directives, etc.) and incorporate them into their products. In the past, OEMs often let resellers navigate these compliance requirements, but now Microsoft itself will ensure its services meet the necessary federal security benchmarks (and presumably attest to them in the contract). GSA’s Lawrence Hale noted that the federal market’s heavy “emphasis on compliance with cybersecurity mandates, FedRAMP, and other regulatory frameworks” was one reason many OEMs preferred to go through resellers before – resellers helped handle those compliance steps. Under OneGov, GSA is working to simplify compliance for OEMs by standardizing requirements, which in turn makes it easier for the OEM to participate directly. The expectation is that Microsoft and others, in agreeing to OneGov terms, accept the unified security and compliance requirements and will work to meet them across all agency deployments.

From an cybersecurity operations standpoint, Microsoft’s GMAS agreement also involves proactive measures: Microsoft is conducting security workshops and training for agencies (e.g. on using Azure’s security features, implementing conditional access, etc.). This shows an expectation that partners (Microsoft in this case) will actively help improve agencies’ cybersecurity posture, not just sell them products. It’s a more collaborative approach where the vendor contributes expertise to tackle government-wide risks (like multi-tenant cloud security governance).

On the pricing side, OneGov sets clear expectations of better pricing and cost transparency for the government. By aggregating demand, GSA expects to negotiate deep discounts and “parity with commercial pricing” for federal buyers. Early OneGov agreements have indeed yielded impressive discounts: for example, in July 2025 GSA announced a OneGov deal with Oracle that gives agencies a 75% discount on Oracle’s cloud and software licenses. Similarly, GSA’s agreement with Google secured a 71% price reduction on Google Workspace licenses for federal agencies, projected to save up to $2 billion over three years. These figures demonstrate the scale of savings when the government acts as one customer. While Microsoft’s GMAS discount details were not publicly released, it’s reasonable to expect substantial improvements over the status quo. (Historically, different agencies paid widely varying prices for Microsoft licenses. GSA analyzed agency data and found “the price variation is astounding… almost a random scattershot”, with no consistent advantage even for larger agencies. One agency might be paying far more for the same product than another. OneGov’s remedy is to “get the volume pricing for the entire federal government in one place… and that price will be available throughout the year.”. In effect, Microsoft under GMAS will likely offer a single standardized discount structure (or menu of prices) that all agencies, big or small, can utilize – eliminating the “scattershot” pricing and ad-hoc discounts of the past.)

Furthermore, OneGov agreements address pricing complexities like cloud billing and fees. For example, the Oracle deal eliminated cloud egress fees for agencies (the fees to transfer data out of Oracle Cloud). This kind of term removes a cost barrier that agencies might face in multi-cloud strategies. We might see similar provisions with Microsoft Azure under OneGov – e.g. favorable terms on data transfer, or standardized discounts on Azure services to encourage cloud adoption. The overall pricing expectation is a “common-sense pricing model” that leverages the government’s full buying power to negotiate not just discounts but also to reduce cost-adders and duplication. GSA describes it as leveraging full purchasing power to “negotiate cost savings, reduce redundancy, and streamline IT acquisition.”.

In terms of compliance expectations for partners (resellers/integrators) under OneGov, any partner that continues to play a role (as a subcontractor or service provider to the OEM) must align with the new normal. For instance, if a reseller is implementing Microsoft 365 at an agency under Microsoft’s OneGov contract, that reseller may need to meet Microsoft’s subcontractor requirements and federal standards. This could include having personnel with security clearances for certain projects, adhering to CMMC/NIST 800-171 controls if handling federal data, and ensuring no conflicts of interest under the new consolidated contract. Microsoft and GSA will likely vet partners more centrally now. Also, since OneGov contracts are government-wide, partners must be prepared to service multiple agencies under one agreement, which might entail broader compliance checks (e.g. ensuring the partner is registered in SAM.gov and not debarred, meeting any supply chain security rules that the prime must flow down, etc.). One positive note is that compliance could actually be easier in some ways – instead of navigating the nuances of 10 different agency-specific contracts, a partner will operate under one standardized set of terms (the OEM’s prime contract). GSA is aiming to streamline compliance by having one master agreement rather than many. So partners must adapt to those master terms.

To summarize, under OneGov and the GMAS Microsoft agreement, cybersecurity is front and center – Microsoft must meet heightened security obligations (encryption, data protection, incident reporting) and help agencies strengthen their defenses. Pricing is standardized and improved, ending the patchwork of deals and giving even small agencies access to big-agency discounts (e.g. enterprise-level pricing for all). And compliance with federal IT requirements is handled more uniformly – with FedRAMP, security mandates, and other regs built into the contract so that every agency gets the benefit of those protections by default. The expectation for Microsoft and its partners is to uphold these standards across all implementations, creating a more secure and cost-effective environment for federal IT.

Transition Timeline and Contract Vehicles

The OneGov initiative began in 2025, but its implementation will roll out over several years and through specific contracting mechanisms. As of mid-2025, GSA had already executed or announced several OneGov pilot agreements: the Microsoft GMAS agreement-in-principle (Jan 2025), a Google Workspace pricing deal (early 2025), Adobe and Salesforce agreements (mentioned by GSA), and an Oracle agreement (July 2025). These early agreements suggest that GSA is initially using short-term agreements or BPAs to quickly lock in savings. For example, the Oracle deal offering 75% off licenses was noted to run “through November” 2025 – likely to align with the end of the federal fiscal year or to serve as a bridge while a more permanent contract is put in place.

Going forward, we can expect GSA to formalize these deals into longer-term contract vehicles that agencies will use. The likely approach is via the GSA Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) program or government-wide acquisition contracts: GSA could add these negotiated terms as MAS modifications or establish Blanket Purchase Agreements (BPAs) under the MAS. For instance, GSA might award a MAS BPA to Microsoft as the principal vendor for Microsoft cloud/software, which all agencies can order from. This BPA would incorporate the standardized pricing and terms from the GMAS agreement. In parallel, GSA might do similar for other vendors (e.g. an Oracle BPA, a Salesforce BPA, etc., each under OneGov). This approach leverages existing contract infrastructure (the MAS schedule) but consolidates orders through a central vehicle instead of many separate agency BPAs. Another possibility is creating new Government-Wide Acquisition Contracts (GWACs) specifically for these major OEMs. However, since speed is important, piggybacking on the MAS (which Microsoft’s partners already utilize) is a logical path.

Transition for Agencies: Agencies will gradually transition from using their own contracts to using the OneGov contracts. There isn’t an immediate mandatory switch, but the advantages (huge discounts, better terms) provide a strong incentive. GSA is promoting these deals and even providing “hands-on support to agencies through the Contract Review Service” to help them adopt the new terms. That is, GSA will assist contracting officers in mapping their current procurements to the new OneGov vehicles. We may see guidance or memos from OMB or GSA encouraging agencies to use the OneGov agreements for any new Microsoft (or other OEM) purchases, rather than negotiating on their own. Over FY2025 and FY2026, as existing contracts expire, agencies can migrate to the centralized contracts to get the better pricing. GSA’s OneGov announcement positions GSA as the “governmentwide hub” for IT shared services, meaning agencies will rely on GSA’s vehicles rather than creating their own.

Timeline Highlights:

- Q1 2025: Agreement in Principle with Microsoft (GMAS) signed Jan 2025. GSA begins socializing OneGov concept.

- Q2 2025: OneGov Strategy officially unveiled April 29, 2025. Google and Microsoft deals referenced as already in place. GSA Acting Administrator calls OneGov a “bold step” aligning with Executive Orders.

- Q3 2025: Additional agreements: e.g. Adobe, Salesforce (mentioned in press), Oracle (announced July 7, 2025). GSA conducts industry webinars (e.g. June 2025 webinar with Lawrence Hale) to gather feedback and explain the model.

- Late 2025: GSA likely formalizes Microsoft GMAS into a contract vehicle (possibly a BPA effective FY26). Oracle’s temporary deal through Nov 2025 suggests a new longer-term contract will follow. GSA expanding OneGov to more vendors and perhaps hardware by end of 2025. Hale indicated they are still in “information-gathering” stage as of mid-2025 for how best to implement broadly, implying that 2025 is a transition/pilot year.

- 2026 and beyond: Expansion of OneGov into other IT categories (hardware, services) as planned. We could see OneGov-like master contracts for laptops, mobile devices, network equipment, etc., where OEMs like Dell, Cisco become primes. Also, refinement of the model based on feedback – e.g. adjustments to ensure small-business subcontractor goals are met. By 2026, the initial software agreements (which might be 3-year deals) will be well underway, and GSA will measure savings and efficiencies gained to report to stakeholders.

For Microsoft partners specifically, the timeline means that FY2025 was a turning point: large federal Microsoft licensing contracts (like Department-level Enterprise Agreements) will gradually funnel into the GMAS structure. If you are a Microsoft reseller or integrator serving government clients, you likely saw changes in late 2024–2025 (e.g. new amendments requiring you to team with Microsoft on proposals). Microsoft itself might have adjusted its sales strategy to center everything on the GSA master agreement, with agencies either buying direct from Microsoft via GSA or through Microsoft’s chosen fulfillment partners under that contract. By the end of 2025, many agencies would plan their FY26 Microsoft renewals through the new channel.

In terms of contract vehicles: GSA has indicated that “future phases could reshape GWACs, IDIQs, and other contract vehicles”. This hints that programs like NASA SEWP, CIO-CS, or even agency-specific IDIQs might be impacted. If OneGov achieves its promise, agencies won’t need to run separate procurement competitions for, say, a Microsoft enterprise agreement – they would simply use the GSA OneGov contract. So, contract vehicles that previously facilitated such purchases might see reduced usage. GSA’s own Multiple Award Schedule (MAS) will likely be the backbone for much of this (since OneGov is managed by GSA, it makes sense to leverage the MAS program to execute it). Indeed, Wiley’s legal alert on OneGov noted it falls in line with an Executive Order on “consolidating procurement through GSA”. This implies GSA wants agencies to use GSA contracts (Schedule, GWACs) versus outside vehicles. OneGov is an embodiment of that consolidation.

Summary of Transition: Starting in 2025, agencies begin moving to new OneGov contracts for Microsoft and other major IT providers as those contracts become available. This transition will likely continue into 2026 as agencies’ existing agreements lapse. Microsoft partners must transition from selling via myriad channels to aligning under the GMAS framework (either by working directly with Microsoft or ensuring their GSA Schedule pricing matches the new standard). GSA will monitor and fine-tune these arrangements. By acting as one buyer, the federal government aims to save money (through bulk discounts), tighten security (through uniform standards), and simplify procurement (no more duplicative solicitations). OneGov, as of 2025, is an ambitious start toward that vision, and Microsoft’s partnership via GMAS is a cornerstone of its initial success.

Have a Question ?

Fill out this short form, one of our Experts will contact you soon.

Talk to an Expert Today

Call Now